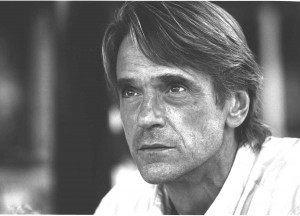

60 year-old actor Jeremy Irons is a patron of the Prison Phoenix Trust, which teaches yoga and meditation to prisoners in the UK’s and Ireland’s jails (www.prisonphoenixtrust.org).

Which cause do you feel most passionately about?

Probably the Prison Phoenix Trust. Without injecting a huge amount of money, it helps those inside vent their anger, and build a habit to support them both in prison and when they get out.

Why should we help prisoners?

Most prisoners are people who’ve been knocked on the head constantly by life: bad parenting, bad schooling…. life’s clobbered them and they’ve gone  inside. We need to stop the circle of people of getting inside, getting out, being unemployed, having bad relationships, having children who are brought up in this atmosphere, who then go inside themselves. Yoga can help people develop self worth, calm themselves, and learn to hold down a position in society.

inside. We need to stop the circle of people of getting inside, getting out, being unemployed, having bad relationships, having children who are brought up in this atmosphere, who then go inside themselves. Yoga can help people develop self worth, calm themselves, and learn to hold down a position in society.

Do you ensure that your donations are used effectively?

As far as I can. I read the accounts and the newsletters. There is a very direct flow of funds with the Phoenix Trust. I worry about giving to larger charities because of the infrastructure in the countries they work in, where money can get hived off.

Do you make impulse donations?

I do give money to people on the street, not to make them go away, nor because I think they’ll spend it wisely, but to make them feel that they are surrounded by compassionate people.

What do you get out of your giving?

I’m one of the most fortunate people in the country really, but I believe that it’s essential to try to attain balance in every element of life. By giving a percentage away, there’s a feeling that I am, in some way, adjusting the balance. Also we’re all taxed fairly heavily. We have no choice where that money goes, and it’s quite nice to feel you’ve made a choice when you give money to this or that organisation.

Are prisons useful?

I don’t think our prisons are, no. We’ve gone badly wrong with our education system. Single parenting is now acceptable, although we know it’s not as efficient for bringing up children as double parentage. We’ve lost any power to discipline difficult children, so it has become difficult to explain that you can be an individual but, to make society work, we have to follow certain rules. As a result, we’ve lost the interwar society of good morals, standards and manners. Prison is the sharp end of that whole enormous shift. We’ve created a system where people are likely to fall by the wayside, and when they do we just chuck them away. Then, because we don’t put enough money or thought into prisons, people come out pretty much the same as they went in. Prison life is too soft. Prisons should be horrible – very hard work, really tough – but also a repairing process. You should come out understanding the rules you have to play by, and why those rules are there.

Copyright The Financial Times Ltd